It would probably make sense to say I’ve been radicalized about women’s health issues by getting breast cancer, but the odd truth is that I got breast cancer smack in the middle of my radicalization.

In the fall of 2013, at the hands of my friend Patrick and to my great fortune, I walked backwards into doing some freelance writing for the Center for Reproductive Rights, a global legal human rights organization that defends reproductive freedom around the world. It’s an incredibly exciting and challenging job.

We fight for expanding abortion rights, ending child marriage and genital mutilation, reducing maternal mortality rates, and improving access to contraception, accurate sex education, and reproductive health care—including screening for cervical and breast cancer. It’s not an easy fight–the issues are systemic and deeply divisive, entrenched in politics as well as cultural and socioeconomic biases, definitely not always dinner table conversation. But it’s a really good fight.

This past fall, with Benny starting Kindergarten and the world opening up a little bit for me, I was able to start working on a closer-to-fulltime basis. The Center is based in Manhattan, but I am able to work from my little desk here in Greensboro and dance with the amazing, high-paced New York (and Bogota and DC and Geneva and Nairobi and Kathmandu!) staff via Skype and phone and a zillion emails and occasional in-person trips.

I am the Center’s writer and editor, and a lot of my work comes down to story telling. Our lawyers and policy experts are engaged at all levels of the court system and on Capitol Hill and at the UN and a number of other international human rights bodies, so it can get pretty wonky at times. Amazing, but definitely wonky.

As part of the communications team, my job is to help engage our base by making our work a little more accessible to the average socially conscious women’s rights supporter. I get to focus on raising up the stories of the women whose personal experiences capture the big-picture efforts we exert across the globe. The 25-year-old woman in El Salvador who is serving a 30-year homicide sentence after suffering a late miscarriage. The clinic worker in Uganda who watches desperate women die from unsafe DIY abortions every week. The terrified immigrant mother in rural Texas who has found lumps in her breast but, due to drastic cuts in reproductive health funding and clinic access, cannot find a reachable physician that can see her.

I’ve even been able to share my own mother’s story—about her great relief at being able to get an abortion in 1974, shortly after Roe v. Wade legalized the procedure—so that she could go back to college and finish her degree.

Engaging with and trying to fully understand the complexities of these stories—the ten million valid reasons women do what they do and a system that can positively crush you if you are missing something as seemingly small as transportation, a social security number, or an extra month’s rent to cover the average cost of an abortion—has definitely changed the way I think about the world.

Two of the very first thoughts I had after receiving The Phone Call from the radiologist with my biopsy results was: Holy Moly, what if I hadn’t gone to the doctor when I felt that lump? and THANK GOD we have great health insurance. The first is luck and privilege. The second is straight-up privilege. And, well—neither insurance nor the accessibility of essential care should have anything to do with either one.

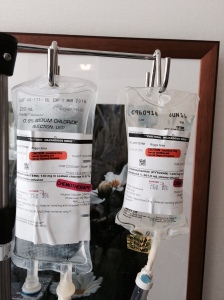

Tomorrow I go back to Duke for my second chemo treatment. This cycle has gone pretty well overall, so I’m hopeful about the next one—although I’ve been prepared that there is a cumulative effect. And it’s challenging to put yourself back in the path of something that makes you feel so diminished, on purpose—the gross sandpaper mouth, the crazy body aches, the constant undercurrent of fatigue, the eddies of nausea. At least last time there was an element of the unexpected.

I’m a little concerned about my ability to keep working through all this. Already I am working a really reduced load—and my bosses could not be more understanding and patient and supportive (another huge plus to working for a women’s health rights organization!)—but I work on a freelance basis, which means by the hour, and if I’m not working, I’m not earning. Yet, we still need to pay for afternoon child care and all the copays—and all our regular stuff. I have to keep working, for more reasons than that it gives each day meaning and focus—although it does.

Just this afternoon I received an EOB in the mail from our (great) insurance saying that I owe a $1371 copay on the $11,000 Nuelasta shot I had three weeks ago—and am about to have again this Saturday.

How do people do this? I’m not trying to bemoan our financial situation—we will be fine and are fortunate to have savings and resources and John’s job and benefits and generous people bringing us food constantly—but I know we are afloat on some piece of jetsum that we happened to bump into and the idea of being an undocumented, uninsured mother with lumps in her breast and no car or education or money in a rural border town in Texas where the nearest doctor is dozens of miles away and has no available appointments for months–what that means for her, her family; what it says about how we treat the most vulnerable among us–makes me feel like I’m going to have a panic attack.

Thankfully my insurance keeps me deep in Xanax.

bly would not–although I felt the keen eyes of the hazmat-suited nurse peeping in on me during the crucial 7-10 minute window. I had a little “wasabi nose” from the second bag of chemo–a weird burning in the front of the face like you just had a big too-quick bite of sushi, but it was minor. I got a little flush

bly would not–although I felt the keen eyes of the hazmat-suited nurse peeping in on me during the crucial 7-10 minute window. I had a little “wasabi nose” from the second bag of chemo–a weird burning in the front of the face like you just had a big too-quick bite of sushi, but it was minor. I got a little flush T and bone scans that show no evidence of metastasis at this point. Yipee!! There’s some drama I’d rather not re-live anytime real soon. Of course, I am aware that is also my future.

T and bone scans that show no evidence of metastasis at this point. Yipee!! There’s some drama I’d rather not re-live anytime real soon. Of course, I am aware that is also my future.